Imagine that humanity was placed on trial to decide whether we’re fundamentally good or fundamentally evil. I’m not talking about nice Mr Jones down the road, or nasty Mrs Smith round the corner. I mean humanity itself – everything we’ve done as a species. All the random kindness and altruistic sacrifice, the feats of engineering and imagination, weighed up against all the selfish exploitation and sadistic abuse, the horrors of murder and genocide. The good, the bad, our crimes and potential, everything we’ve done in the past and everything we might do in the future, decided once and for all. You stand in final judgement on the accomplishments of homo sapiens.

How do you find? Are we basically good, with a few bad traits? Are we essentially evil, with some redeeming qualities? And are we collectively worthy of a pardon, or should we all be condemned?

You might think this is a rather abstract question to ask, but in reality it cuts past all the nonsense and gets right to the heart of who we are. Why do we live? Why do we keep living? Why do we have children? Why don’t we gratify all our desires, irrespective of cost? The answer, inevitably, lies in our beliefs about the nature of humanity – on whether we think people, at root, are good or evil. And only when we’ve made that judgement can we decide who we want to be and how to live our lives.

Is human nature evil?

Before passing judgement, you might consider that the question has been conclusively answered by Western civilisation, which is grounded on the assumption that human nature is evil. Whether it’s art, religion, politics, law, economics, education, industry or simple entertainment, the underlying belief is that, left to our own devices, we would rapidly descend into a hell of rape and murder. If there is one universal belief about the meaning of life, it is that there are beasts in our nature, and we must learn to control them or they will destroy us.

This pessimism about humanity’s worth is embedded in the foundation story of Western culture. Mankind was pure, and innocent, and living in harmony with Nature in the Garden of Eden. But we sinned, and were cast out to a life of toil and struggle and ultimate death. And what happened next? The first child ever born on Earth was murdered by the second. It got worse from there, until God had to destroy his creation with a flood. And we’ve been sinning ever since. The evil in humanity’s nature, and our resulting fall from grace, is the central precept of Christianity, and by extension, the whole of Western civilisation.

This fall from grace metaphor isn’t confined to Abrahamic religion, either. The Ancient Greek poet Hesiod, in the eighth century BCE, told a remarkably similar story. There was first a Golden Age, in which humans lived like gods, knowing no suffering or toil. In the subsequent Silver Age, humans were inferior to the gods, and the men had to work. They degenerated further through the Bronze Age and the Age of Heroes, until humanity completed the fall in the current Iron Age, where people are selfish and evil, and know only struggle and sorrow. It’s the same story: once, we were innocent; now we are corrupted; and there is no going back.

More recently, we’ve tried to rationalise and control the capacity for evil in human nature. In the seventeenth century, Thomas Hobbes argued that in his natural state, ‘every man is Enemy to every man’, and such a life was ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.’ Society, and civilisation itself, were invented to free humanity from ‘continual fear, and danger of violent death’. In his influential model of human nature, knowing the evil we’re capable of, humans voluntarily gave up some of their freedom to belong to a society that protected them from the chaos. The idea of the ‘social contract’ between government and governed had been born.

In the early twentieth century, the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud discovered (perhaps invented) the seat of human nature, the unconscious mind, or id, a place dominated by the libido and death drive that gives us an innate, insatiable desire to eat, mate and destroy. He saw his job as wrestling with ‘the most evil of those half-tamed demons that inhabit the human beast’, and that was early in his career, before a lifetime of treating patients led him to conclude that ‘I have found little that is “good” about human beings on the whole’.

We are all rapist serial killers inside, so the theory goes, and it is the ego and super-ego that, mostly, keep these desires in check. We learn to suppress these instincts in order to gain the benefits of peaceful coexistence with our neighbours, but they’re still there, just below the surface, always ready to break free, as they did to such devastating effect in the twentieth century.

Any lingering naivety about the reality of human nature was obliterated in the 1960s when Stanley Milgram’s electric-shock experiments famously demonstrated the extent to which ordinary people would murder a stranger in obedience to an authority figure. The Nazis, he showed, were not an aberration of history – they were ordinary human beings, no different from you and me. As were the monsters of Stalin’s regime, and those of Mao and Pol Pot.

So deeply ingrained is this belief in humanity’s innate evil that in 1970, the visionary director Stanley Kubrick could quite openly say that, ‘Man isn’t a noble savage, he’s an ignoble savage. He is irrational, brutal, weak, silly, unable to be objective about anything where his own interests are involved—that about sums it up. I’m interested in the brutal and violent nature of man because it’s a true picture of him. And any attempt to create social institutions on a false view of the nature of man is probably doomed to failure.’

There is a continuous line of thought running from the Enlightenment to today that argues our society is structured to control and punish the evil of human nature, either by social convention or formal proscription. Without the threat of prison, and the controlling mechanisms of society and government, we’d all be a bunch of violent monsters raping and murdering our way across the landscape.

You might think this is an exaggeration, but consider the ways this idea is codified in the widespread beliefs of our society. Under the right circumstances, it is said, anybody can become a murderer, or a rapist, or a drug addict. After all, only nine meals stand between mankind and anarchy. And every school child knows that without external controls, and a reliable food supply, the green and pleasant hills of the Home Counties or New England would turn into Lord of the Flies. Like a murderer in a prison cell, human nature needs to be caged for everyone’s safety.

Even in a society that has rejected religion, the belief in humanity’s essential evil crops up wherever you look. Think about Climate Change arguments, for example. Humanity is a virus that destroys its host, say the activists. No other organism expands beyond an ecosystem’s ability to sustain it. We’ve upset the balance of Nature, and if we become extinct it’s because we deserve it. We have selfishly and knowingly destroyed the planet and our children’s futures for short-term gratification, and we steadfastly refuse to change our habits, dooming us all to destruction. The argument has a beautifully sound clarity: Nature is good, and innocent, and pure; humanity, once a part of Nature, now destroys Nature; therefore humanity is evil. This is as similar as secularism comes to the biblical story of Genesis, though I imagine that, when pressed, most would deny it.

This is the narrative underlying Western civilisation. Some people think being cynical about human nature makes you modern, and edgy, and progressive, but such people have no idea what they’re talking about. Since time immemorial, the great and the good have characterised humanity as evil and the species as being in decline. By this token, we should conclude that human nature is evil, and we should be condemned.

But is that really the case? After all, as Plato argued, ‘Good people do not need laws to tell them to act responsibly, while bad people will find a way around the laws.’

And does this focus too much on individual rather than collective responsibility?

Perhaps we should frame it in another way.

Is human nature innocent, while human society is evil?

An added complexity, and a way of delaying making a judgement on humanity’s good or evil, is to separate individual humans from the mass of humanity, and decide whether humans are themselves evil or merely ciphers for the larger scale structural evils of society.

It stands to reason that no child can be evil, in the same way that no animal can be evil. Children, like animals, don’t have the capacity to make reasoned judgements about their behaviour. Like mankind before the fall, children are innocent, and pure, and without sin.

But as they grow, the world moulds them. Their parents, their culture, society itself, shapes them into something with the capacity for evil. That’s why parents are so worried about messing up their kids. By the logic of this argument, a person who steals, or rapes, or murders, is a victim of their upbringing, a slave to their background. It is not their nature that is bad, but the environment that formed them. Society creates the evil it then punishes, and the person, the individual human, is nothing more than a pawn.

In other words, hate the game, don’t hate the player.

While this might seem like a modern idea, again it is nothing new. This was a hot-button topic in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as a reaction to Hobbes’ assertion that humanity in its natural state was brutish and violent and needed to be controlled by society. While some glamorised the ‘noble savage’ as a superior being, people like John Locke, Lord Shaftesbury (Anthony Ashley-Cooper), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued instead that humanity in a state of nature was a blank slate, neither good nor evil. It was civilised man, living in society, who had the capacity for good and evil, and the verdict was almost unanimous that society tended towards evil. As the immortal opening lines of Rousseau’s The Social Contract declared in 1762: ‘Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains.’ This in turn led Karl Marx in the nineteenth century and Michel Foucault in the twentieth to argue that human society is an oppressive force, using structural power to dominate, oppress and control.

Proponents of the modern Social Justice Movement owe more to these thinkers than they realise. Propped up by free-market capitalism and the patriarchy, the structure of Western society, they argue, is undoubtedly oppressive and amoral – institutionally racist, sexist, heteronormative, trans-phobic and classist. And it’s no small elite jealously guarding their wealth and their privilege as they fight to keep others down – it’s every man and woman of every race and sexuality and gender identity that accepts and perpetuates and is infected by society. The very foundations of our way of life are evil and must be torn down, to pave the way for more government, more legislation and more control over how we think and behave. It is society, and the evil people in it, who are guilty, not the inherent nature of humanity.

You might be convinced by this argument that people are innocent but society is bad, and it’s certainly easier, and more comforting, to pardon individual humans while condemning human society as an whole, but you have to ask whether it’s really possible, or even desirable, to separate the two. Human society, after all, is a product of human individuals, the sum total of our human nature. And does it really matter if the evil lies in human nature or human society when the end result – human evil – is the same?

Blaming society does not let you off the hook. You have to decide whether the collective endeavour of humanity is good or evil, and there’s no way out of it.

Or is there?

How do we decide what’s good and what’s evil?

You could always sidestep the issue and argue that there is no such thing as good or evil, except insofar as individual societies decide what constitutes good and evil. You might even claim, with some justification, that the world has moved beyond such concepts as good and evil, with their religious overtones and binary positions. This social constructionist approach is very forgiving, and seems reasonable – a religious society will have different definitions of good and evil than a secular society, after all, as will a village in medieval Europe and a city in modern Sweden. But claiming that good and evil are in the eye of the beholder, and that the constraints placed on behaviour are situational – in essence, that good and evil don’t exist – is not only amoral and cowardly, but wrong, from both a philosophical and evidentiary standpoint.

It is a fallacy to suggest, as religious people and many atheists do, that without a divine figure defining good and evil, humans will decide it for themselves. All of the philosophers already mentioned, with the exception of Foucault, while struggling with the nature of good and evil, still believed humans had an innate moral sense, a common understanding of right and wrong that transcends society and is part of our nature. This ‘moral sense’, the source of all goodness, was sympathy, or, as Rousseau defined it, the ‘innate repugnance to see others of his kind suffer.’

Where’s the evidence for this? Probably in a central idea of peoples separated by time, space, religion and culture: the so-called Golden Rule.

See if any of these quotations seem similar:

- ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you’ (Christianity).

- ‘Love your neighbour as yourself’ (Judaism).

- ‘As you would have people do to you, do to them; and what you dislike to be done to you, don’t do to them’ (Islam).

- ‘Choose thou for thy neighbour that which thou choosest for thyself’ (Baha’u’llah).

- ‘Those acts that you consider good when done to you, do those to others, none else’ (Hinduism)

- ‘Hurt not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful’ (Buddhism).

- ‘A man should wander about treating all creatures as he himself would be treated’ (Jainism).

- ‘Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself’ (Confucianism).

- ‘Regard your neighbour’s gain as your own gain, and your neighbour’s loss as your own loss’ (Taoism).

- ‘Whatever is disagreeable to yourself do not do unto others’ (Zoroastrianism).

- ‘That which you hate to be done to you, do not do to another’ (Ancient Egypt).

- ‘Treat others as you would treat yourself’ (Mahabharata)

- ‘Avoid doing what you would blame others for doing’ (Ancient Greece).

- ‘Treat your inferior as you would wish your superior to treat you’ (Ancient Rome).

Even Wicca, the religion of witchcraft, says, ‘that which ye deem harmful unto thyself, the very same shall ye be forbidden from doing unto another’. This is an undeniably conclusive expression of the moral sense that exists in human nature, an injunction of how we should act, and a guide to define good and evil.

It is this knowledge of good and evil, and our capacity to choose how we act, that separates us from the animals. We do not mindlessly follow the dictates of our nature, but decide how we are going to behave in respect to our morality. This is so important that it bears repeating. Without a universal knowledge of morality, and without free will, the question about whether humanity is good or evil would be meaningless, because good and evil would not exist.

Since we’ve established that humanity knows the difference between good and evil – that this knowledge is natural and innate – we’re coming closer to having to make that final judgement on humanity.

Are humans responsible for the evil that humanity does?

Since humans have both a moral sense and free will, does it follow that they are therefore responsible for the evil that they do? Is there a difference between individual and collective responsibility? And why is it that the injunction to treat others as you’d treat yourself is so often ignored?

It could be argued that the Golden Rule is applied much more consistently within societies than between societies. In the case of war, the most obvious expression of individual and collective human evil, a soldier can continue to treat his own side as he would treat himself, and therefore be good, while killing the other side, which makes him evil. That said, the tradition of just war holds that rival combatants are morally equal – that is, the soldier on one side, by engaging in war, consents to kill and risk being killed, and the soldier on the other side does the same, meaning they are treating the other side as they would themselves. Warfare, therefore, does not constitute an evil at the level of the individual – but collectively, there is no denying the evil that warfare inflicts.

It must also be pointed out that while humans, by dint of our reason, are distinguished from Nature, we are still part of Nature. The dichotomy of Nature/good, humanity/bad greatly oversimplifies things, perhaps deliberately so. Nature is not in a state of balance – it is in a state of perpetual chaos typified by the merciless struggle for existence. Nature is cruel and brutal, red in tooth and claw. Warfare is not unique to civilisation or even humanity – the eminent primatologist Dr Jane Goodall was horrified to witness a four year ‘war’ between two groups of chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, in Gombe National Park in the 1970s, suggesting an uncomfortable continuity between our animalistic ancestors and our modern selves.

And what of individual evil? We all see ourselves as moral beings, so how is evil even possible? As individuals, the injunction to do unto others requires that we not only have the empathy to understand the effects of our behaviour on others, but we have to understand ourselves and our own power, which very few people do. Ignorance, narrow-mindedness, misinformation, misunderstanding, and dissimulation – our ability to use our reasoning faculties against ourselves to argue that black is white and white is black – are responsible for far more evil in society than deliberate intent.

There are very few people who choose evil. But that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. It is reckoned that 4% of people are sociopaths, utterly lacking in compassion, empathy or conscience. That 4% causes untold suffering in the world, not least because they exploit the weakness that exists in the remaining 96%. Our moral sense, so obvious at rest, is susceptible to the pressures of our biological limitations, so that when we’re tired, when we’re hungry, when we’re afraid and confused, addled by alcohol or drugs, when we’re in pain and when we’re desperate, we’re less likely to follow the dictates of our conscience. We give in to our primitive needs. We’ve all done things that, in the cold light of day, we know to be wrong. We are all guilty of evil.

Intentional or not, collective or individual, that does not excuse us. We are responsible for our evil, because we know better. It therefore follows that we are also responsible for our good.

And therein lies the key to the whole issue of this debate. If we are to own our evil, we must also own our good. If our evil is diabolical and reprehensible, then our choice to do good is noble and heroic. So how do we weigh up the good against the bad?

Is there good in humanity?

The human capacity for evil is limitless – that is a given – but so too is the human capacity for good. As we’ve seen, there is a Golden Rule governing human interaction, that of respect for others, which is unlikely to exist in a species that is inherently evil. And while examples of evil are daily thrust into our faces by a media industry wedded to pessimism, you don’t have to look very far to find examples of human goodness much closer to home.

The neighbour who takes us in when we lock ourselves out; the boy who helps an elderly stranger put her shopping in the car; the hundreds of thousands of blood donors who sacrifice their time, and submit to pain, to ensure people they’ll never meet have a chance at survival. Every day, a multitude of kindnesses go unrecorded and unremarked, but if you look for them, you’ll discover that they’re everywhere.

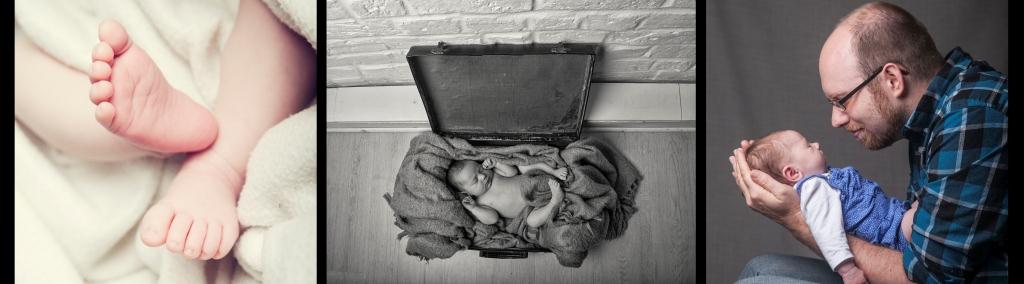

There is no greater example of human goodness than the act of parenting. For our children we sacrifice our health, our time, our money, our security, and even our safety – there are very few parents who would not give up their lives to save their children from harm. While it is true that you can find similar altruistic self-sacrifice in the animal kingdom, the difference is that, without free will, an animal’s parenting is innate, and instinctive, and therefore it can’t take credit for it. It is our very awareness of our mortality, it is our conscious choice to sacrifice ourselves, that makes human parenting noble.

There is no reason to have a child. Logically, rationally, using our reason, the benefits to us as individuals of not having children far outweigh whatever benefits we accrue from having them. But we still have children. Why? Because we hope it’ll all work out? I used to believe that hope made the world go round, but then I realised that hope is an admission of helplessness. It’s an expression of futility and defeat. Faith is what makes the world go round. Not faith in a religious sense, but faith that things will be better, that we will overcome the beasts in our nature, and that we will never be defeated by them.

We are told, repeatedly, that we are killers, that we are destroyers, that our nature is violent. We are the worst of the worst. Yet killers comprise such a small fraction of society, it’s hardly even worth measuring. Parents, on the other hand, are everywhere. Every day, everywhere across the face of the planet, ordinary humans take the conscious decision to sacrifice some of their own vitality in order to create something pure, and turn it into something better. We talk about human evil with every breath; but our actions say something different. We believe in human goodness. We have faith in the goodness of the future, or else we would never have children.

That is the truth about humanity. We’re not as evil as we like to think, and we’re a lot better than we realise. We may be in the gutter, but we’re looking at the stars.

So what is the final judgement of humanity?

It’s time to make your decision. If you’re struggling, consider a famous story about this very thing, that of Robert Louis Stephenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: ‘In each of us, two natures are at war – the good and the evil. All our lives the fight goes on between them, and one of them must conquer. But in our own hands lies the power to choose – what we want most to be we are.’

Perhaps I should answer first. It’s always easier when someone else leads the way.

Are we good? Yes. Are we evil? Yes. Should we be condemned? Without a doubt. And should we be pardoned? Absolutely.

We are a contradiction as a species. We are part of Nature, and stand above it. We are capable of the ultimate self-sacrifice, and also the most selfish tyrannical abuse. We are neither good nor evil, but both at the same time, and to deny one or the other would be to do us a disservice. It is the evil in our nature that allows us to claim the good; and the good that makes us responsible for the evil.

The evil we do is undeniable and sometimes so overwhelming that we cannot conceive of the good. But as one who came face to face with evil in the Soviet Gulags, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was under no illusions that we are either one or the other. ‘The battleline between good and evil runs through the heart of every man,’ he wrote.

The true act of rebellion is not to embrace humanity’s evil and give way to nihilism; it is to accept humanity’s goodness. That we are not wholly evil, despite everything tending in that direction, is testament to that goodness. It is our ability to choose to rise above the evil in our nature – it is the very fact that we are redeemable – that gives me faith in humanity.

So how do you find?

I’m afraid I don’t find the question particularly interesting (once I’ve established that people do good and people do bad, I move on to thinking about how to encourage the good, discourage the bad and ensure that we correctly recognise both).

Stanley Milgram’s results weren’t as clear as you may believe. According to https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg23731691-000-the-shocking-truth-of-stanley-milgrams-obedience-experiments/

privately, in an unpublished note in the archives, Milgram worried whether his experiments were “significant science or merely effective theatre… I am inclined to accept the latter interpretation”.

LikeLike

Hi Andrew,

Thanks for the comment. I think the question itself is as old as the hills – it’s the answer that matters. TV channels and bookstores are filled with stories about war, crime, murder and genocide, all of them trying to explain or understand why people do so much evil, but I don’t think human evil needs much to explain it. Human goodness, on the other hand, that’s the mystery. Why do we do good even in situations where it’s easier and more beneficial to us to do evil?

For example, earlier this year an experiment was carried out in which 17,000 ‘lost’ wallets containing the owner’s phone number were handed in at establishments in 40 countries. When the wallets were empty, they were returned 40% of the time. When they contained a small amount of money, they were returned 51% of the time. And when they contained a large amount of money, they were returned 72% of the time. People are more honest than we realise.

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/jun/20/honesty-is-majority-policy-in-lost-wallet-experiment

As regards Milgram, I’m not sure it matters whether his results were meaningful or not (I’m inclined to think they were, since I’ve seen the experiment replicated multiple times with similar results). The important point is that people believe they’re meaningful. It’s the same with Freud’s unconscious – whether or not it’s true that there’s a beast inside us all (and I can’t think we could ever prove or disprove its existence), people believe there is. We have all kinds of mechanisms to explain (and excuse) human evil, but far fewer to explain the roots of human goodness.

Again, thanks for taking the time to comment,

Gillan

LikeLike

[…] not a Christian myself, I was raised as one and I still try to follow the Golden Rule of treating others how I’d wish to be treated myself. It forms the hard nugget at the centre […]

LikeLike